How to Properly Calculate Force: Essential Methods for Accurate Results in 2025

“`html

How to Properly Calculate Force: Essential Methods for Accurate Results in 2025

Understanding how to accurately calculate force is fundamental in physics, engineering, and many real-life applications. Mastering the principles behind force not only enhances comprehension of the concepts of mass, acceleration, and other key elements, but also provides practical insights for scientific exploration and real-world problem-solving. This article delves into the various methods for calculating force, emphasizing the vital role of Newton’s Second Law, various force types, and forces in nature, ensuring you can confidently apply these concepts in 2025 and beyond.

Fundamentals of Force Calculation

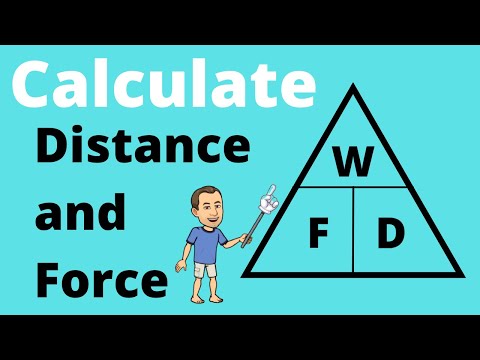

Force calculation is rich with complex yet essential concepts in physics. At its core, force is a vector quantity, influencing motion, direction, and interactions of objects. To fully grasp how to calculate force, one must engage with Newton’s Second Law, which states that the force acting on an object is equal to its mass multiplied by the acceleration (F = ma). Through understanding these foundations, you can effectively measure force in various contexts and applications.

Understanding Force as a Vector Quantity

Force is classified as a **vector quantity** because it has both magnitude and direction. This means when calculating force, one must consider how direction influences the overall effect. For example, if an object is pushed in one direction with a certain strength (or magnitude), that push results in a specific force impacting its motion. When two forces act on an object in different directions, vector addition techniques, including the use of **free body diagrams**, are invaluable in determining the net force acting on that object. Analyzing these vectors helps in understanding **balanced forces** and **unbalanced forces**, which are crucial in predicting the motion of objects.

Newton’s Second Law: The Core Equation

Newton’s Second Law is foundational in **force calculations**: \( F = ma \). Here, **mass** represents the amount of matter in an object, and **acceleration** is the rate of change of velocity. To illustrate this, consider a scenario where a cart with a mass of 10 kg is pushed with an acceleration of 2 m/s². Applying Newton’s second law yields a force of 20 N (F = 10 kg x 2 m/s²). This law not only serves as a generalization for many practical applications but also aids in analyzing more complex systems where multiple forces may intersect, leading to dynamic scenarios requiring strategic force assessments.

Mechanics of Measuring Force

Measuring force typically requires various units, depending on the context. The standard unit of force is the Newton (N), but other units such as pounds (lb) or dynes are also prevalent. Understanding **unit conversion** is critical when comparing forces in different systems. In this section, we’ll address significance of accurate measurements, useful tools, and methods employed in dynamic-day scenarios.

Force Measuring Tools

Several instruments can facilitate the accurate measurement of force in experiments and practical applications. Common tools include **spring scales**, which operate based on Hooke’s Law, converting the force of a force’s action to a measurement value expressed in Newtons or pounds. Furthermore, **force sensors** can provide digital readings valuable in experimental setups, enhancing the precision of collected data. Knowing how to apply these devices effectively allows one to tackle complex scenarios, be it in academic settings or real-world dynamics.

Practical Example: Measuring Frictional Force

Frictional forces, vital to understanding **mechanical advantages** and various practical applications, can be measured through experiments. For instance, if a block is placed on a surface and a known pulling force is applied until the block moves, the static friction can be calculated by measuring the maximum force applied before motion occurs. By calculating the coefficient of friction, one can derive insights into the friction force by using \( F_f = \mu F_n \), where \( F_f \) is frictional force, \( \mu \) is the coefficient of friction, and \( F_n \) is the normal force acting on the object.

Advanced Force Applications in Real Life

Understanding force has vast implications in daily applications ranging from engineering to biomechanics. By mastering the calculations, not only can one appreciate the underlying principles of motion but also harness these insights for innovative solutions and advancements in various fields.

Applications in Engineering and Design

In engineering, force calculations are essential for designing structures that withstand various stresses. For instance, engineers apply concepts of force balance and dynamic equilibrium when determining the specifications for buildings, bridges, and roads. Also, projects involving **mechanical advantage** hinge on an understanding of force in systems of simple machines. By harnessing principles of **torque** and predictions based on calculated forces, unique designs that enhance efficiency while ensuring safety can be realized.

Force in Sports Science

In the realm of sports science, understanding force calculations support athlete performance enhancement. Metrics such as **momentum**, techniques of **impulse**, and the impact of **gravitational forces** during athlete maneuvers inform training strategies. Coaches apply force analysis to draw insights on optimizing athlete performance by refining movements to minimize injury occurrences while maximizing efficacy. Each athlete’s unique force characteristics help in customizing training plans for peak performance.

Key Takeaways

- Force is a vector quantity crucial in understanding dynamics and kinematics.

- Newton’s Second Law, represented as F = ma, is fundamental in calculating impact and movement.

- Various methods and tools aid in measuring force accurately across multiple disciplines.

- Applications extend from engineering design to sports science, showcasing the practical usage of force understanding.

- Balanced and unbalanced forces significantly influence the resulting motion of objects.

FAQ

1. What is the relationship between mass and acceleration in force calculations?

The relationship between mass and acceleration is defined by Newton’s Second Law, which states that the force acting on an object is equal to the mass of the object multiplied by its acceleration (F = ma). This means that as mass increases, for a given force, acceleration will decrease, indicating an inverse relationship.

2. How do I distinguish between net force and resultant force?

Net force refers to the total force resulting from combining all individual forces acting on an object, accounting for direction. Resultant force, in contrast, typically refers to the single force that demonstrates the combined effect of multiple forces, particularly in vector analysis. Both terms play crucial roles in understanding an object’s dynamics.

3. What are the different types of forces acting on objects?

Forces can be categorized into several types: **gravitational force**, **tension**, **frictional force**, **applied force**, and **normal force**, among others. Each type plays a critical role depending on the context of the situation—like friction in motion, or normal force in static objects placed on surfaces.

4. How does friction influence force measurements?

Friction talks directly to how forces act when surfaces come into contact. Understanding the coefficient of friction is essential for calculating the accompanying forces, especially important in simulations and experiments, ensuring that applied forces account for resistant motion due to friction.

5. Can forces be measured in different units? If so, how do I convert them?

Yes, forces can be measured in various units like Newtons (N), pounds (lbs), or dynes. Converting between these units involves using their specific conversion factors (1 Newton = 0.2248 pounds; 1 pound = 4.448 Newtons). Familiarity with these conversions is important for effectively discussing and comparing force in scientific contexts.

“`